Tadalis SX

Order line tadalis sx

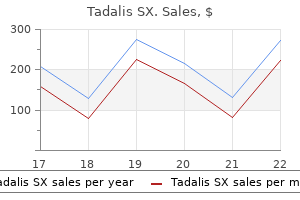

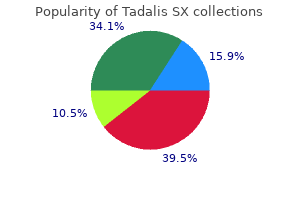

Is an involved circumferential resection margin following oesphagectomy for cancer an important prognostic indicator? Recurrence of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus after curative surgery: rates and patterns on imaging studies correlated with tumour location and pathological stage impotence juice recipe buy tadalis sx from india. Factors affecting postoperative course and survival after en bloc resection for esophageal carcinoma. Pattern of recurrence following radical oesophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. Prospective randomised study on radiotherapy and surgery in the treatment of oesophageal carcinoma. Pattern of recurrence after oesophageal resection for cancer: clinical implications. Pathologic response after neoadjuvant therapy is the major determinant of survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Pattern of recurrence following complete resection of esophageal carcinoma and factors predictive of recurrent disease. Symptoms, investigations and management of patients with cancer of the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction in Australia. Ovarian management guidelines published by major national and international organisations since the completion of the previous radiotherapy utilisation study in July 2003 have been reviewed. Level of evidence the indications of radiotherapy for ovarian have been derived from evidence-based treatment guidelines issued by major national and international organisations. The guidelines reviewed are those published after the previous radiotherapy utilisation study completed in July 2003 up to March 2012. Epidemiology of cancer stages the epidemiological data in the ovarian cancer utilisation tree have been reviewed to see if more recent data are available through extensive electronic search using the key words ‘epidemiology ovarian cancer’, ‘incidence’, ‘local control’, ‘ovarian cancer stage‘, ‘radiotherapy treatment’, ‘recurrence’, ‘survival’, ‘treatment outcome’ in various combinations. The proportion used for the model (12%) was based on similar metastatic site distribution in the studies from Royal Marsden Hospital, London (13) and Harvard Medical School, Boston (15); the model effect of the data variability was tested though sensitivity analysis. Estimation of the optimal radiotherapy utilisation From the evidence on the efficacy of radiotherapy and the most recent epidemiological data on the occurrence of indications for radiotherapy, the proportion of ovarian cancer patients in whom radiotherapy would be recommended is 3. Estimation of the optimal combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy utilisation Concurrent chemoradiation is not recommended for treatment of ovarian cancer. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Available at: cancer gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/ovarianepithelial/HealthProfessional 2012 [cited 2012 May 22]; 5. Available at: ycn nhs uk/html/downloads/ycn gynae-guidelinesclinical-aug2011 pdf 2011 [cited 2012 May 15]; 6. Consolidation treatment of advanced ovarian carcinoma with radiotherapy after induction chemotherapy. Effective palliative radiation therapy in advanced and recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Epidemiology of cancer stages the published recent epidemiological data on pancreatic cancer have been identified through extensive electronic search using the key words ‘epidemiology pancreatic cancer’, ‘pancreatic cancer stage‘, ‘incidence’, ‘local control’, ‘radiotherapy treatment’, ‘survival’, ‘treatment outcome’ in various combinations. For our model the proportion estimate (60%) of the most recently studied Corsini et al study (8) been used. The incidence of attributes used to define indications for radiotherapy Population or Attribute Proportion of Quality of References subpopulation population with Information of interest the attribute All registry cancers Pancreatic cancer 0. Members of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group, Earle C, They R, reviewers. Guidelines for the management of patients with pancreatic cancer periampullary and ampullary carcinomas. On behalf of British Society of Gastroenterology, Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, Royal College of Pathologists, Special Interest Group for Gastro-Intestinal Radiology. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. Treatment of locally unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas: comparison of combined-modality therapy (chemotherapy plus radiotherapy) to chemotherapy alone. Pain relief with short-term irradiation in locally advanced carcinoma of the pancreas. Updated Guidelines the following clinical practice guidelines for the management of prostate cancer were identified. A number of changes to the tree design have occurred as a result of changes in evidence and guideline recommendations. Changes to Epidemiological Data the epidemiological data in the prostate cancer utilization trees have been reviewed to identify whether more recent data are available through extensive electronic searches. These have been applied to the early branches in the trees for which national or state level data on cancer incidence rates and stages are available. In 2008, prostate cancer accounted for 18% of all cancer in Australia (31) (Table 3). As a result there are multiple treatment options for patients with non-metastatic cancer and uniform agreement between guidelines regarding treatment indications was frequently not the case. This leaves the recommendations open for several treatment options, whereas for most other tumour sites, treatment recommendations are often more definitive. Life Expectancy the guidelines recommend that radical treatment should be reserved for patients likely to live long enough to benefit (4) (6) (9) (13) (16) (18) (24) and recommend that there is a life-expectancy of at least five to ten years before radical treatment is considered. Patients with a shorter life expectancy have been shown to be unlikely to benefit from radical treatment of their prostate cancer (36) (37) (38). Page | 313 Patient Preference Where evidence is lacking for a benefit from one particular treatment option over another, the treatment choice lies with the patient. In order to model patient choice, patient choice studies or patterns of care studies may be used. A disadvantage of both approaches is that they contain biases; patients use a wide variety of sources of information to arrive at a preference, with the patient’s physician having greatest influence (42). It has been demonstrated that different professional groups have little agreement regarding the optimal treatment choice (43). A specific disadvantage of using patterns of care studies is that there is a wide variation in treatments administered between countries (41) (44) and even within countries (45) (46), reflecting the fact that patterns of care studies reveal what treatment is being administered and perhaps what is more accessible, not necessarily the optimal treatment that should be administered. Patterns of care studies are biased by such issues as geographical access to treatments, and to medical practitioners and by varying costs to patients of different treatments. For the purposes of this utilization tree, patient choice studies, despite the above-listed limitations, were used to determine the proportion of patients choosing between equivalent treatment options, with sensitivity analyses performed to assess the effect on the model of varying the patient preference. Patient choice studies used or considered in previous optimal utilisation models for prostate cancer (1) (2) (3) (47) have disadvantages that include: not all treatment options being offered (48) (49) (50) (51), hypothetical scenarios being offered to well men without prostate cancer (48) (49), small sample size (49) (50), or inadequate pre-choice counselling without consultation with both a radiation oncologist and a urologist (48) (49) (50) (52) (53). All patients discussed all management options with a urologist, a radiation oncologist, and a specialist nurse, were given comprehensive information leaflets, and then were offered a second appointment to further discuss matters. The previous model used patient disease risk grouping, and there has been little change in the proportion of patients presenting with metastatic disease. Sensitivity Analyses Univariate sensitivity analyses were undertaken (Figures 3 and 4) to assess any changes in the optimal utilisation rate that would result from different estimates of the proportions of patients with particular attributes as mentioned in Table 3. These options are dichotomised in the Utilisation Trees as the TreeAge software only allows two branches to be tested with sensitivity analysis with any one test. As discussed above, the default for the tree was set at 0%, but sensitivity analysis was performed to increase this to 100% to model the two diametrically opposed views presented in the guidelines. The greatest contributors to the variability were uncertainty in patient preference. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Evidence-based information and recommendations for the management of localised prostate cancer. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Locally Advanced and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. The Use of Conformal Radiotherapy and the Selection of Radiation Dose in T1 or T2 Prostate Cancer. Adjuvant radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy for pathologic T3 or margin-positive prostate cancer. Post-prostatectomy radiation therapy: Consensus guideline of the Australian and New Zealand Radiation Oncology Genito-Urinary Group. Australian and New Zealand Faculty of Radiation Oncology Genito-Urinary Group: 2010 consensus guideline for definitive external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Guideline for the Management of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: 2007 Update. American College of Radiology and American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology.

Buy discount tadalis sx 20mg

Middleton et al (2011) showed that training stroke unit staff in the use of standardised protocols to manage physiological status can significantly improve outcomes impotence because of diabetes buy discount tadalis sx line. The management of blood pressure after acute ischaemic stroke remains an area with little evidence to guide practice (see Section 3. There is no evidence for the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in stroke (Bennett et al, 2014) nor for the use of supplemental oxygen in normoxic patients (Roffe et al, 2011) and from the evidence available, the Working Party recommends that mannitol for the treatment of cerebral oedema should not be used outside of a clinical trial. There is very little trial evidence on which to base the management of hydration in acute stroke. A Cochrane review of the signs and symptoms of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people (Hooper et al, 2015) concluded that there is little evidence that any one symptom, sign or test, including many that clinicians customarily rely on, have any diagnostic utility for dehydration. There is good evidence that a multi-item dysphagia screening protocol that includes at least a water intake test of 10 teaspoons and a lingual motor test was more accurate than screening protocols with only a single item (Martino et al, 2014). There is good evidence from a systematic review (Kertscher et al, 2014) that the investigation of dysphagia with instrumental assessments providing direct imaging for evaluation of swallowing physiology help to predict outcomes and improve treatment planning. In contrast to acute myocardial infarction, tight glycaemic control has not been shown to improve outcome in stroke (Gray et al, 2007) and studies have warned against aggressive lowering with insulin infusions due to the risk of hypoglcaemia. This has led the Working Party to recommend a broadening of the target range for blood glucose in acute stroke from 4-11 mmol/L to 5-15mmol/L. Two recent studies showed no clinical benefit from the prophylactic use of antibiotics in dysphagic stroke patients and thus routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended (Kalra et al, 2015, Westendorp et al, 2015). B Patients with acute stroke should have their clinical status monitored closely, including: ‒ level of consciousness; 48 ‒ blood glucose; ‒ blood pressure; ‒ oxygen saturation; ‒ hydration and nutrition; ‒ temperature; ‒ cardiac rhythm and rate. C Patients with acute stroke should only receive supplemental oxygen if their oxygen saturation is below 95% and there is no contraindication. D Patients with acute stroke should have their hydration assessed using multiple methods within four hours of arrival at hospital, and should be reviewed regularly and managed so that normal hydration is maintained. E Patients with acute stroke should have their swallowing screened, using a validated screening tool, by a trained healthcare professional within four hours of arrival at hospital and before being given any oral food, fluid or medication. F Until a safe swallowing method is established, patients with dysphagia after acute stroke should: ‒ be immediately considered for alternative fluids; ‒ have a comprehensive specialist assessment of their swallowing; ‒ be considered for nasogastric tube feeding within 24 hours; ‒ be referred to a dietitian for specialist nutritional assessment, advice and monitoring; ‒ receive adequate hydration, nutrition and medication by alternative means. G Patients with swallowing difficulties after acute stroke should only be given food, fluids and medications in a form that can be swallowed without aspiration. H Patients with acute stroke should be treated to maintain a blood glucose concentration between 5 and 15 mmol/L with close monitoring to avoid hypoglycaemia. I Patients with acute ischaemic stroke should only receive blood pressure-lowering treatment if there is an indication for emergency treatment, such as: ‒ systolic blood pressure above 185 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure above 110 mmHg when the patient is otherwise eligible for treatment with alteplase; ‒ hypertensive encephalopathy; ‒ hypertensive nephropathy; ‒ hypertensive cardiac failure or myocardial infarction; ‒ aortic dissection; ‒ pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. J Patients with acute stroke admitted on anti-hypertensive medication should resume oral treatment once they are medically stable and as soon as they can swallow medication safely. K Patients with acute ischaemic stroke should receive high intensity statin treatment with atorvastatin 20-80 mg daily as soon as they can swallow medication safely. L Patients with primary intracerebral haemorrhage should only be started on statin treatment based on their cardiovascular disease risk and not for secondary prevention of intracerebral haemorrhage. Therapeutic positioning, whether in bed, chair or wheelchair, aims to reduce skin damage, limb swelling, shoulder pain or subluxation, and discomfort, and maximise function and maintain soft tissue length. Good positioning may also help to reduce respiratory complications and avoid compromising hydration and nutrition. Evidence to recommendations One systematic review (Olavarria et al, 2014) examined four small non-randomised trials of head position in acute ischaemic stroke patients which studied cerebral blood flow using transcranial Doppler but did not report on functional outcome. B Healthcare professionals responsible for the initial assessment of patients with acute stroke should be trained in how to position patients appropriately, taking into account the degree of their physical impairment after stroke. C When lying or sitting, patients with acute stroke should be positioned to minimise the risk of aspiration and other respiratory complications, shoulder pain and subluxation, contractures and skin pressure ulceration. Very early mobilisation led to greater disability at three months with no effect on immobility-related complications or walking recovery. The trial included people with previous stroke, severe stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage and those who were thrombolysed, if they required help to mobilise and were expected to remain in hospital for at least three days. It excluded those who were medically unstable or with significant previous disability. This was carried out by nurses or therapists an average of six times per day, and included an average daily amount of 31 minutes of mobilisation by a physiotherapist measured over 14 days or until transfer of care if earlier. The more beneficial usual care was still early but slightly later, less frequent and at a lower dose. Almost everyone (93%) was mobilised within 48 hours of onset, 59% within 24 hours and 14% within 12 hours, by nurses or therapists an average of three times per day, and including an average daily amount of 10 minutes of mobilisation by a physiotherapist. A subsequent exploration of dose hypothesised that early mobilisation might be best delivered in short, frequent amounts (Bernhardt et al, 2016) but this requires further research. B Patients with difficulty moving early after stroke who are medically stable should be offered frequent, short daily mobilisations (sitting out of bed, standing or walking) by appropriately trained staff with access to appropriate equipment, typically beginning between 24 and 48 hours of stroke onset. Mobilisation within 24 hours of onset should only be for patients who require little or no assistance to mobilise. B Patients with immobility after acute stroke should not be routinely given low molecular weight heparin or graduated compression stockings (either full-length or below-knee) for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis. C Patients with ischaemic stroke and symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism should receive anticoagulant treatment provided there are no contraindications. D Patients with intracerebral haemorrhage and symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism should receive treatment with a vena caval filter. It intentionally overlaps with Chapters 3 (acute care) and 5 (long-term management) and relates to multiple settings including acute stroke units, stroke rehabilitation units, early supported discharge services and other community rehabilitation services. Some recover rapidly and completely and may no longer be present when care is transferred from the in patient setting. Other problems will persist over weeks, months and years and may even increase over time as the person’s priorities alter and an awareness develops of the challenges of life after stroke. Service organisation and the delivery of rehabilitation are typically focused in the first months of stroke and often fail to meet the long-term and evolving needs of people with stroke. Over time the nature of rehabilitation will shift from restorative to compensatory and adaptive approaches but rehabilitation should not end solely because natural recovery appears to have reached a plateau. This guideline provides a range of recommendations on the management of specific losses and limitations that arise following the brain damage that occurs from stroke. For clarity and to promote a patient-centred approach, this chapter is structured alphabetically by problems. To implement these recommendations as intended, guideline users must do so in the context of the recommendations in Chapter 2 that cover the principles of rehabilitation (Sections 2. It is also important to note that several rehabilitation interventions have been included in Chapter 3 as they should occur in the first hours or days of stroke and prevent the development of complications (Sections 3. Likewise, several interventions from Chapter 4 should be considered for delivery as part of ‘further rehabilitation’ (Section 5. The evidence base for stroke rehabilitation is increasing but substantial gaps remain. Commissioning more rehabilitation research has the potential to greatly improve service delivery and patient outcomes. The resultant loss of function can have implications on a person’s ability to live independently at home and is therefore a key part of stroke rehabilitation. B People with limitations of personal activities of daily living after stroke should be referred to an occupational therapist with experience in neurological disability, be assessed within 72 hours of referral, and be offered treatment for identified problems. C People with stroke should be offered, as needed, specific treatments that include: ‒ dressing practice for people with residual problems with dressing; ‒ as many opportunities as appropriate to practice self-care; ‒ assessment, provision and training in the use of equipment and adaptations that increase safe independence; ‒ training of family/carers in how to help the person with stroke. The Working Party excluded for methodological reasons one small, non-randomised trial of community-dwelling people with stroke which substituted a portion of physiotherapy time with virtual reality games (Singh et al, 2013). This increased the number of journeys made and had a lasting effect, but practical limitations in collecting the data on number of journeys may have limited the reliability of the outcome measure. The intervention did not affect the primary (quality of life) or any other outcome, and was not cost-effective. B People with stroke who cannot undertake a necessary activity safely should be offered alternative means of achieving the goal to ensure safety and well-being. Healthcare professionals therefore need to discuss and give advice on fitness to drive. Evidence to recommendations A recent Cochrane review of four small trials of interventions to improve on-road driving skills after stroke concluded there was insufficient evidence to guide practice (George et al, 2014). No trials evaluated on road driving lessons, and one study investigated simulator training.

Syndromes

- Strawberry hemangiomas may appear anywhere on the body. They are most common on the neck and face. These areas consist of small blood vessels very close together.

- When your child gets permanent teeth, he or she should begin flossing each evening before bed.

- Fever

- Decreased language ability (aphasia)

- · You recently had sexual contact with someone who has hepatitis A.

- Forceful or constant vomiting

- Washing of the skin (irrigation) -- perhaps every few hours for several days

- Mandatory written reporting: A report of the disease must be made in writing. Examples are gonorrhea and salmonellosis.

- Your vision is hazy or blurry and you cannot focus.

Generic 20mg tadalis sx visa

Even if Regular physical activity 0·63 (0·44–0·88) 0·78 (0·55–1·11) this apparent reduced risk is not real erectile dysfunction young causes purchase tadalis sx overnight, the finding suggests Alcohol intake that risk rapidly reduces after stopping smoking, 1–30 drinks per month 0·75 (0·57–1·00) 0·89 (0·66–1·18) indicating that smoking cessation is an essential >30 drinks per month or binge drinker 1·36 (1·00–1·86) 1·59 (1·13–2·23) component for any stroke prevention programme. Models are adjusted for age, sex, region, hypertension, alcohol intake, smoking status, components of a Mediterranean diet29—was associated physical activity, diet, diabetes mellitus, cardiac causes, depression and psychosocial stress, and waist-to-hip ratio. Unlike for myocardial Information about the source of the data was missing for 19 controls (1%). The relation between ischaemic stroke and especially important in people of alcohol intake and stroke seems complex: our data 45 years or younger. These to 52%, an estimate that is consistent with a previous findings are mostly consistent with previous epi systematic review. For subjective risk factors, Our study provides important and new information on we noted more consistency between patients and proxy the association of lipoproteins and apolipoproteins with respondents for psychosocial stress than for depression, stroke risk. Findings of epidemiological studies have been which might indicate that stress is more easily identified inconsistent, with most studies failing to identify an by a close relative than is depression. Ideally, controls would be drawn from the association has been reported in some studies. Although our overall findings are consistent, proteins, which are known to be stable in acute stroke,35 hospital-based controls could underestimate the true were stronger risk factors for ischaemic stroke than were association for some risk factors. However, we recruited patients across a convincing evidence that apolipoproteins are associated wide range of stroke severities, and we did not note with risk of ischaemic stroke. A particularly striking convincing differences in key risk factor associations by finding in our study was that the reduction in risk of stroke severity. Clinicians provided a presumed aetiology for has been reported in previous studies,34 but this relation is most cases of ischaemic stroke, but the vast majority of poorly understood and will be further explored in phase 2 cases did not undergo vascular imaging or cardiac of our study. Although atrial fi3 brillation was diagnosed in occurrence of diagnostic testing could increase the more than a fifth of cases in high-income regions, the proportion of patients reported to have presumed small prevalence was much lower in southeast Asia and India. For this reason, we have not proportion of patients undergoing cardiac investigations. In most regions, the cost of diagnostic proportion of patients with underlying, asymptomatic investigations precludes their routine clinical use. However, in phase 2, we will attempt to increase the Our study has several potential limitations, including routine use of diagnostic testing in all sites, especially those inherent to a case-control design (eg, selection bias, large vessel imaging, in all sites. However, for almost all risk additional 10000 case-controls pairs, which will be Philippines A L Dans*, M V Sulit, E Collantes, M del Castillo, also needed to establish the independent contribution of D Morales, C Lagayan, M Candela, A Roxas, I Tan, C Recto, G Lau. Poland A Czlonkowska*, D Ryglewicz*, M Skowronska, M Restel, Importantly, phase 1 has shown that such an undertaking A Bochynska, K Chwojnicki, M Kubach, A Stowik, M Wnuk. Sudan A S A Elsayed*, A Bukhari, Z Sawaraldahab, H Hamad, M ElTaher, A Abdelhameed, In conclusion, a large international epidemiological M Alawad, D Alkabashi, H Alsir. Sweden A Rosengren*, M Andreasson, study of stroke that requires routine neuroimaging is B Cederin, C Schander, A C Elgasen, E Bertholds, K Bengtasson. Our Thailand Y Nilanont*, N Samart*, T Pyatat, N Prayoonwiwat, findings suggest that ten simple risk factors are associated N Phongwarin, N C Suwanwela, S Tiamkao, R Tulyapronchote, S Boonyakarnkul, S Hanchaiphiboolkul, S Muengtaweepongsa, with 90% of the risk of ischaemic and intracerebral K Watcharasakslip, P Sathirapanya, P Pleumpanupat. Uganda C Mondo*, J Kayima, M Nakisige, S Kitoleeko, that reduce blood pressure and smoking, and promote P Byanyima. All authors Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer contributed to the collection of data, discussions and interpretation of Ingelheim, CoAxia, D-Pharm, Fresenius, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, the data, and to the writing of the report. All authors had full access to Knoll, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Medtronic, MindFrame, Neurobiological data, and reviewed and approved the drafts of the report. No medical Technologies, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Paion, Parke-Davis, Pfizer, Sanofi writer or other people participated in the study design, data analysis, or Aventis, Sankyo, Schering Plough, Servier, Solvay, Thrombogenics, Wyeth, writing of this report. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and committee membership fees from the Population Health Research Institute, Canada. Australia J Varigos*, G Hankey*, to cover recruitment costs, research staff, study materials and equipment, A Claxton, W Y Wang. A Lameira, M Friedrich, L C Marrone, J F K Saraiva, A C Carvalho, I Rocha, V L Laet, M Coutinho, F Brunel, L Melges, C R Garbelini, Acknowledgments A C Baruzzi, D A Reis. Stroke in developing countries: can the epidemic be J Wang, L Wang, J Wang, J Shi, W Gu, H Shao, Y Hu, H Song, R Ji, L Hao, stopped and outcomes improved? Preventing stroke: saving lives G Sanchez, R Garcia, J Arguello, N Ruiz, D I Molina, A Sotomayor, around the world. Tackling the global burden of stroke: the need T Truelsen*, H K Iversen, C Back, M M Petersen. India P Pais*, D Xavier*, A Sigamani, N P Mathur, intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population: a systematic P Rahul, D Rai, A K Roy, G R K Sarma, T Mathew, G Kusumkar, review. Intracerebral haemorrhage: V Atam, A Agarwal, N Chidambaran, R Umarani, S Ghanta, G K Babu, a need for more data and new research directions. Lancet Neurol G Sathyanarayana, G Sarada, S Navya Vani, R Sundararajan, 2010; 9: 133–34. Lancet 2004; A Chouhan, B N Mahanta, T G Mahanta, G Rajkonwar, S K Diwan, 364: 937–52. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction stroke: an overview of published reviews. Lancet 2008; reduction or cessation of cigarette smoking: a cohort study in 371: 1612–23. Experience from a multicentre stroke register: a 30 Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Variations in the use of diagnostic procedures after acute 32 Iso H, Baba S, Mannami T, et al. Improving global vascular risk Relationships between lipoprotein components and risk of prediction with behavioral and anthropometric factors. Potential new risk factors for ischemic stroke: what is artery atherosclerosis in an elderly multiethnic population: the their potential? High-density lipoprotein burden and mortality: estimates from monitoring, surveillance, and cholesterol and ischemic stroke in the elderly: the Northern modelling. Trends in stroke and coronary heart disease in the apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. The intended audiences are prehospital care providers, physicians, allied health professionals, and hospital administrators. Methods—Members of the writing group were appointed by the American Heart Association Stroke Council’s Scientifc Statements Oversight Committee, representing various areas of medical expertise. Strict adherence to the American Heart Association confict of interest policy was maintained. Members were not allowed to participate in discussions or to vote on topics relevant to their relations with industry. The members of the writing group unanimously approved all recommendations except when relations with industry precluded members voting. Prerelease review of the draft guideline was performed by 4 expert peer reviewers and by the members of the Stroke Council’s Scientifc Statements Oversight the American Heart Association makes every effort to avoid any actual or potential conficts of interest that may arise as a result of an outside relationship or a personal, professional, or business interest of a member of the writing panel. Specifcally, all members of the writing group are required to complete and submit a Disclosure Questionnaire showing all such relationships that might be perceived as real or potential conficts of interest. This guideline was approved by the American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee on November 29, 2017, and the American Heart Association Executive Committee on December 11, 2017. Data Supplement 1 (Evidence Tables) is available with this article at stroke. Data Supplement 2 (Literature Search) is available with this article at stroke. Select the “Guidelines & Statements” drop-down menu, then click “Publication Development. A link to the “Copyright Permissions Request Form” appears on the right side of the page. These guidelines use the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association 2015 Class of Recommendations and Levels of Evidence and the new American Heart Association guidelines format. Results—These guidelines detail prehospital care, urgent and emergency evaluation and treatment with intravenous and intra-arterial therapies, and in-hospital management, including secondary prevention measures that are appropriately instituted within the frst 2 weeks. The guidelines support the overarching concept of stroke systems of care in both the prehospital and hospital settings. In many instances, however, only limited data exist demonstrating the urgent need for continued research on treatment of acute ischemic stroke. New or revised recommendations that supersede With Acute Ischemic Stroke” in 2013. The purpose of these guide unchanged are reiterated with reference to the previous pub lines is to provide an up-to-date comprehensive set of rec lication.

Buy cheap tadalis sx 20 mg on-line

The cells of the intermediate ous process that begins at the level of the future cer zone differentiate into neurons and glial cells erectile dysfunction treatment for heart patients cheap 20mg tadalis sx amex. Radial vical region, and proceeds both rostrally and caudal glial cells are present during early stages of neuroge ly (O’Rahilly and Müller 1999, 2001). Most radial glial cells transform into astrocytes (2000), however, provided evidence that neural tube (Chap. The neurons send axons into an outer lay closure in humans may be initiated at multiple sites er, the marginal zone. Neural tube defects are the cell bodies, becomes the grey matter, and the ax among the most common of human malformations onal, marginal layer forms the white matter. It devel neural crest cells migrate extensively to generate a ops from the ventricular zone of the rhombic lip, a large diversity of differentiated cell types (Le Douar thickened germinal zone in the rhombencephalic in and Kalcheim 1999; Chap. The subventricular zone is found in the la of the adrenal gland, (3) the melanocytes, the pig lateral and basal walls of the telencephalon. This zone ment-containing cells of the epidermis, and (4) many gives rise to a large population of glial cells and to the of the skeletal and connective tissues of the head. The vertebrate neural plates appears to be highly con alar plates are united by a small roof plate, and the served. The alar plates and mals, for which detailed fate maps are more difficult incoming dorsal roots form the afferent or sensory to obtain. Nevertheless, available data (Rubinstein part of the spinal cord,whereas the basal plate and its and Beachy 1998; Rubinstein et al. The such as the hypothalamus and the eye vesicles arise development of the alar and basal plates is induced by from the medial part of the rostral or prosencephalic extracellular signalling molecules, secreted by the part of the neural plate (Fig. In its turn, the lateral border of this part of the neural plate forms floor plate induces the formation of motoneurons in the dorsal, median part of the telencephalon and the the basal plate. Many other genes are involved in directions: from medial to lateral, and from rostral to the specification of the various types of neurons in caudal (Lumsden and Krumlauf 1996; Rubinstein the spinal cord (Chap. Mediolateral or ven neurons to develop (Windle and Fitzgerald 1937; trodorsal pattern formation generates longitudinal Bayer and Altman 2002). They appear in the upper areas such as the alar and basal plates,and rostrocau most spinal segments at approximately embryonic dal pattern formation generates transverse zones day 27 (about Carnegie stage 13/14). Most likely,the rostrocau development also dorsal root ganglion cells are pre dal regionalization of the neural plate is induced al sent. Dorsal root fibres enter the spinal grey matter ready during gastrulation (Nieuwkoop and Albers very early in development (Windle and Fitzgerald 1990). The meso synapses between primary afferent fibres and spinal derm that follows will form the chordamesoderm motoneurons were found in a stage 17 embryo (Oka and more lateral mesodermal structures. Ascending fibres in the or mesoderm differs from the chordamesoderm also dorsal funiculus have reached the brain stem at in the genes that it expresses. The first descending supraspinal ate neural development by inducing neural tissue of fibres from the brain stem have extended into the an anterior type, i. A second signal from chordamesoderm alone far caudally as the spinomedullary junction at the converts the overlying neuroectoderm induced by end of the embryonic period (Müller and O’Rahilly the first signal into a posterior type of neural tissue, 1990c; ten Donkelaar 2000). The anterior region comprises the forebrain and most of the midbrain,and is characterized by expres 1. The expression of some genes involved in the pattern cb cerebellum, cho chiasma opticum, ec ectoderm, en endo ing of the brain is shown in a dorsal view of the neural plate of derm, ev eye vesicle, hy hypothalamus, is isthmus, m mesen an E8 mouse (c) and in a median section through the neural cephalon, nch notochord, nr neural ridge, pchpl prechordal tube at E10. The arrows indicate the morphogenetic plate, p1, p6 prosomeres, Rthp Rathke’s pouch, r1–r7 rhom processes involved in the closure of the neural tube. Holoprosencephaly,ade later the floor plate) and dorsal (epidermal–neuro fect in brain patterning, is the most common struc ectodermal junction, and later the roof plate) aspects tural anomaly of the developing forebrain (Golden of the neural plate and early neural tube. Lat neural plate such as the anterior neural ridge and the 16 Chapter 1 Overview of Human Brain Development Fig. The mesencephalon is indicated in phalon, npl nasal placode, o occipital lobe, pros prosence light red. The Lateral and medial views of the developing brain are posterior limit of Otx2 expression marks the anterior shown in Figs. In Otx2 knock flexure at the midbrain level, already evident before out mice, the rostral neuroectoderm is not formed, fusion of the neural folds; (2) the cervical flexure,sit leading to the absence of the prosencephalon and the uated at the junction between the rhombencephalon rostral part of the brain stem (Acampora et al. The three main divisions of the brain structures arising from the first three rhombomeres, (prosencephalon, mesencephalon and rhomben such as the cerebellum, are absent. The first part of the telencephalon subject to a wide variety of naturally occurring muta that can be recognized is the telencephalon medium tions (Chap. The mesomeres (M, M1, M2) and Lc locus coeruleus, lge lateral ganglionic eminence, lterm the mesencephalon (mes) are indicated in light red. Asterisks lamina terminalis, mge medial ganglionic eminence, np cran indicate the spinomedullary junction. Frontal, temporal and occipital poles and the insula 1994, 1995a, b; Blaas and Eik-Nes 1996; van Zalen become recognizable (Fig. The extension of the ultrasound techniques to three dimensions has made it possible 1. Anomalies of the ven opened new possibilities for studying the human em tricular system such as diverticula are rare (Hori et bryonic brain. Accessory ventricles of the posterior so greatly improved the image quality that a detailed horn are relatively common and develop postnatally description of the living embryo and early fetus has (Hori et al. ChorP1-4 choroid plexuses of lateral and fourth ventricles, Di diencephalon,Hem cerebral hemisphere,Mes mesencephalon, Rhomb rhombencephalon, 3 third ventricle. Six Morphological segments or neuromeres of the brain primary neuromeres appear already at stage 9 when were already known to von Baer (1828), and were de the neural folds are not fused (Fig. They gradually fade after arranged transverse bulges along the neural tube, stage 15 (Fig. On an isthmic neuromere (I), two mesomeres (M1, M2) ly recently, interest in neuromeres was greatly re of the midbrain, two diencephalic neuromeres (D1, newed owing to the advent of gene-expression stud D2) and one telencephalic neuromere (T) can be dis ies on development, starting with the homeobox tinguished. Neuromere D1 gives rise to the eye vesicles and Each rhombomere is characterized by a unique com the medial ganglionic eminences (Müller and bination of Hox genes, its Hox code. The neu brain stem, the sulcus limitans divides the prolifera romeres of the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain tive compartments into alar and basal plates. On the basis of these findings, in all murine prosomeres alar and basal parts are dis tinguished (Rubinstein et al. Prosomeres P1–P3 form the dien cephalon: P1 is the synencephalon, P2 the paren cephalon caudalis and P3 the parencephalon ros tralis. The alar component of the synencephalon forms the pretectum, that of the caudal paren cephalon the dorsal thalamus and epithalamus and that of the rostral parencephalon the ventral thala mus. Prosomeres P4–P6, together known as a protosegment, form the secondary pros encephalon (Rubinstein et al. The main differences between human and murine neuromeres concern the pro someres. Puelles and Verney (1998) applied the pro someric subdivision to the human forebrain. The subpallium appears as tinuous expansion of the cerebral hemispheres, the medial and lateral elevations,known as the ganglion formation of the temporal lobe and the formation of ic (Ganglionhügel of His 1889) or ventricular emi sulci and gyri and (3) the formation of commissural nences (Fig. The caudal part of the ventricular connections, the corpus callosum in particular. The larger lateral the development of the cerebellum takes place large ganglionic eminence is derived from the telen ly in the fetal period (Fig. The cerebellum aris cephalon, and gives rise to the caudate nucleus and es bilaterally from the alar layers of the first rhom the putamen. Early in the fetal period, the two bres separate the caudate nucleus from the putamen, cerebellar primordia are said to unite dorsally to and the thalamus and the subthalamus from the form the vermis. Both the lateral and the medial ven advocated Hochstetter’s (1929) view that such a fu tricular eminences are also involved in the formation sion does not take place, and suggested one cerebel of the cerebral cortex. V are directed caudally as well as laterally, and thick 2001; Marín and Rubinstein 2001; Chap. The cau en enormously, accounting for most of the early dal part of the ganglionic eminence also gives rise to growth of the cerebellum.

Order on line tadalis sx

Arch Ophthalmol early treatment with interferon beta-1b after a first clinical event 2008; 126: 994–95 statistics on erectile dysfunction order 20 mg tadalis sx otc. Corticosteroids for treating optic clinically isolated syndrome and long-term outcomes: a 10-year neuritis. Central nervous system a prospective study of seven patients treated with prednisone and sarcoidosis—diagnosis and management. Azathioprine: associated optic neuritis: clinical experience and literature review. Massive astrocyte destruction in neuromyelitis optica despite Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 1131–36. Does interferon beta azathioprine in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders with treatment exacerbate neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder? Impact of rituximab on relapse rate and disability immunosuppression for treatment of corticosteroid dependent in neuromyelitis optica. Successful treatment of memory B cells in patients with relapsing neuromyelitis optica over optic neuropathy in association with systemic lupus erythematosus 2 years. Antibody to aquaporin-4 in to pulse cyclophosphamide in neuromyelitis optica: evaluation of the long-term course of neuromyelitis optica. Autologous mesenchymal in neuromyelitis optica: increase in relapses and aquaporin 4 stem cells for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple antibody titers. Please help us to continue to provide free information to people affected by brain injury by making a donation at People with the condition cannot tell the difference between faces, an ability most of us take for granted. They may not even recognise the faces of their closest friends and family, or their own face in the mirror. This can be a cause of great distress, social isolation and loss of opportunities in careers and relationships. The pure form of the condition does not result from generalised difficulties in memory or visual perception and is not associated with mental confusion. Indeed, they can still access all their stored knowledge about a person once they know their name, and they can still recognise other types of objects. However, the pure form of prosopagnosia is very rare, and most people who acquire face recognition difficulties after brain injury experience other cognitive and visual difficulties alongside the condition. This occurs because brain injury tends to affect a number of brain regions, causing multiple difficulties. As face recognition comes so naturally to most people, it can be very difficult for those with normal face processing abilities to understand. A good way to understand it is to think about our ability to distinguish individual animals, such as chimpanzees. Humans find it very difficult to identify chimpanzees unless they have a lot of practise looking at particular individuals. The chimps themselves, however, have no problem telling each other apart but have great difficulty doing the same with humans. It seems we have evolved an ability to expertly identify faces of our own species. The particular pattern of face processing and other cognitive and visual difficulties varies greatly among individuals with prosopagnosia. Many people have problems extracting information other than identity from a face, and may struggle to interpret a person’s gender, age or emotional expression. Most people with prosopagnosia also have difficulties recognising other classes of objects, such as cars, household utensils or garden tools. This can result from visual difficulties in processing angle or distance, or may be caused by poor memory for places and landmarks. Finally, more general visual impairments are frequently observed in people with prosopagnosia, such as the perception of luminance, colour, curvature, line orientation or contrast. Whether experienced alongside other difficulties or in isolation, prosopagnosia generally results from damage to specific brain areas. Typically it is parts of the occipital lobes and temporal lobes involved with perception and memory that are affected, especially a specific region within each temporal lobe known as the fusiform gyrus. There is a fusiform gyrus in both sides of the brain, but it is the one in the right hemisphere that is usually associated with face processing. Some evidence suggests that fusiform gyrus damage tends to bring about difficulties in face perception and recognition, whereas damage to other areas of the temporal lobes is associated with difficulties accessing memories of faces. It has therefore been suggested that there are two subtypes of prosopagnosia, one affecting the way we perceive faces (apperceptive prosopagnosia), and the other affecting our memory for faces (associative prosopagnosia). However, as noted above, it is rare that damage is confined to just one brain area, and prosopagnosia is often accompanied by a range of other cognitive and visual difficulties. This can sometimes make it difficult to interpret the nature of a person’s face processing difficulties according to the two subtypes. Developmental prosopagnosia Interestingly, there also appears to be a developmental form of the condition that has been estimated to affect approximately 2% of the population (approx. Instead, people with developmental prosopagnosia seem to fail to develop the visual mechanisms necessary for successful face recognition. Studies of identical and non-identical twins have also provided more evidence of a genetic basis. A recent study has shown that in face recognition tests the correlation of scores between identical twins was more than double that of non-identical twins. It has been suggested that the developmental form of the condition could be related to other conditions. For example, case reports have documented that some people with developmental prosopagnosia experienced uncorrected visual problems for sustained periods of their childhood. This may be related to impaired social functioning, poor memory and inability to interpret the emotional and mental state of other people. While developmental prosopagnosia shares the same key characteristics as prosopagnosia acquired after brain injury. Research suggests that faces are processed in a unique way, differently to other types of objects. People with normal face recognition abilities appear to process faces ‘holistically’. This means that the face is processed as a whole, taking account of the relationship between features rather than focusing on the features themselves. This is demonstrated by the following three phenomena unique to the perception of faces rather than other objects. The inversion effect Faces are very difficult to recognise when upside down, whereas other objects tend to still be recognisable. Figure 2: the inversion effect the figure above shows human faces and dogs in upright and inverted positions. Research has shown that dogs are much easier to identify when inverted than human faces. This is a lot less of a problem when identifying features of other objects, such as the doors of a house. Figure 3: the part/whole effect the diagram above shows a typical test of whole-face and part-face identification. It is much easier to identify Jim’s eyes when shown in the context of the whole face than when shown separately. This is because when the halves are aligned the brain automatically tries to process the image as a whole face and can no longer identify a specific half. Bush (top half) and Tony Blair (bottom half) in the unaligned condition than when they are aligned. Further evidence for this has come from studies of young children, who seem to have an innate bias towards faces over other objects. Infants as young as a few days old have been shown to have a preference for looking at faces and face-like images, such as patterns resembling two eyes, a nose and a mouth. The children spend far longer looking at these images than other non-face like patterns.

Discount tadalis sx 20 mg mastercard

Cancer survivors should engage in regular physical activity for its many health benefts how erectile dysfunction pills work buy online tadalis sx. For adults with breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer, greater amounts of physical activity after diagnosis help to substantially lower the risk of dying from their cancer. For adults with breast and colorectal cancer, greater amounts of physical activity after diagnosis also help to substantially lower the risk of dying from any cause. Cancer survivors who are physically active have a better quality of life, improved ftness and physical function, and less fatigue. Physical activity also plays a role in reducing the adverse effects of cancer treatment. As a result of cancer and its treatment, some cancer survivors are at increased risk of heart disease, and physical activity can help reduce this risk. As with other adults with chronic conditions, cancer survivors can consult with a health care professional or physical activity specialist to match a physical activity plan to their abilities, health status, and any treatment toxicities. Physical Activity in Adults With Selected Physical Disabilities For many types of physical disabilities, physical activity reduces pain, improves ftness, improves physical function, and improves quality of life. People with disabilities that affect their ability to walk or move about beneft from physical activity. Physically active people who have Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, a spinal cord injury, or a stroke have better physical function, including walking ability, than less active adults with the same condition. These improvements have been shown with multicomponent physical activity programs that included aerobic activity (commonly walking), muscle-strengthening, and balance-training activities. Potential specifc benefts include: Parkinson’s disease—Improved physical function, including walking, balance, muscle strength, and disease-specifc motor scores. Benefts can be seen with recent or older injuries and across severities of spinal cord injury. Adults with physical disabilities can consult with a health care professional or physical activity specialist to match a physical activity plan to their abilities. Jessica: A 28-Year-Old Woman Who Is Pregnant Jessica is 16 weeks pregnant, and her pregnancy is progressing normally. Before she became pregnant, Jessica did some light and moderate intensity physical activity, but she did not meet the key guidelines. She discusses her plans with her doctor, who tells her it is safe for her to increase her activity level as long as she keeps him informed throughout her pregnancy. Jessica joins a prenatal yoga class at her local hospital, which meets once a week. She also starts walking during her lunch break for 30 minutes 3 days a week, for a total of 90 minutes of moderate intensity activity. As she begins to gain strength and endurance, Jessica adds a 60-minute walk and 30 minutes of muscle-strengthening activities with resistance bands each weekend, modifying exercises to avoid lying on her back. With these additions, Jessica has reached 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week and participates in 1 day of muscle strengthening. As Jessica’s pregnancy progresses, she notices lower back pain that intensifes on longer walks, so she replaces her longer walk with swimming. She continues using resistance bands and attending her prenatal yoga class until her baby is born. Ines: An 83-Year-Old Woman With Osteoarthritis Ines has been active all her life, but osteoarthritis in her hip and knee have started to slow her down. Ines communicates regularly with her doctor, who agrees that staying active can help to reduce her level of pain, as well as improve her physical function and health-related quality of life. Because of her age and ability level, Ines typically judges the intensity of her activity based on her own level of exertion. Ines does the equivalent of at least 160 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, plus muscle-strengthening activities 2 days a week. The video includes 20 minutes of moderate-intensity movements, including stepping, marching, and walking in place. The mall provides a safe, indoor place to walk with clear paths, even surfaces, and places to sit down if needed. Additional Considerations for Some Adults 85 Chris: A 53-Year-Old Man With Multiple Sclerosis His goals: Chris is a 53-year-old man with multiple sclerosis who sets a goal of doing 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity on 4 days a week (a total of 120 minutes a week). Starting out: Chris starts where he feels safe and comfortable, using a stationary bike at his gym. On the stationary bike, Chris does moderate intensity physical activity for 20 minutes on 2 days each week. In order to track his progression, he takes note of his intensity level and tries to keep his level of effort at a 5 or 6 on a scale of 0 to 10. Making good progress: Two months later, Chris is comfortably using a stationary bike at a moderate intensity for 30 minutes on 3 days a week. In addition to his time on the stationary bike, Chris has started to attend a water exercise class specifcally for individuals with multiple sclerosis. The class focuses on multicomponent physical activity and meets one evening a week for 30 minutes. Reaching his goal: Eventually, Chris surpasses his goal and works up to 160 minutes a week of moderate intensity aerobic activity, including 30 minutes of stationary bicycling 4 times a week, a water ftness class for 30 minutes once a week, and a 10-minute brisk walk after work once a week. Raymond: A 42-Year-Old Man With Type 2 Diabetes Raymond is a 42-year-old man with type 2 diabetes. Recently, at the recommendation of his physician, he started paying more attention to his activity levels. He received a step counter for his birthday, and he uses it to track his daily activity and stay motivated. After a few months of increasing his physical activity, Raymond now does the equivalent of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week, plus muscle-strengthening activities 3 days a week. Active and Safe Although physical activity has many health benefts, injuries and other adverse events do sometimes happen. Other adverse events can also occur during activity, such as overheating and dehydration. The good news is that scientifc evidence strongly shows that physical activity can be safe for almost everyone. Still, people may hesitate to become physically active because of concern they will get hurt. For these people, there is even more good news: people can take steps that are proven to reduce their risk of injury and adverse events. The key guidelines in this chapter provide advice to help people do physical activity safely. Specifc guidance for particular age groups and people with certain conditions is also provided. Key Guidelines for Safe Physical Activity To do physical activity safely and reduce risk of injuries and other adverse events, people should: Understand the risks, yet be confdent that physical activity can be safe for almost everyone. Choose types of physical activity that are appropriate for their current ftness level and health goals, because some activities are safer than others. Increase physical activity gradually over time to meet key guidelines or health goals. Inactive people should “start low and go slow” by starting with lower intensity activities and gradually increasing how often and how long activities are done. Protect themselves by using appropriate gear and sports equipment, choosing safe environments, following rules and policies, and making sensible choices about when, where, and how to be active. Be under the care of a health care provider if they have chronic conditions or symptoms. Even so, studies show that only one such injury occurs for every 1,000 hours of walking for exercise, and fewer than four injuries occur for every 1,000 hours of running. Both physical ftness and total amount of physical activity affect risk of musculoskeletal injuries. Follow the other guidance in this chapter (especially increasing physical activity gradually over time) to minimize the risk of injury. Choose Appropriate Types and Amounts of Activity People can reduce their risk of injury by choosing appropriate types of activity. The safest activities are moderate intensity, low impact, and do not involve purposeful collision or contact. Walking for exercise, gardening or yard work, bicycling or riding a stationary bike, dancing, swimming, and golf are activities with the lowest injury rates. In the amounts commonly done by adults, walking (a moderate intensity and low-impact activity) has a third or less of the injury risk of running (a vigorous-intensity and higher impact activity). Sports that involve collision or contact, such as football, hockey, and soccer, have a higher risk of injuries, including concussion.

HL-362 (Forskolin). Tadalis SX.

- Use as eye drops for glaucoma (increased pressure in the eyes).

- What other names is Forskolin known by?

- Use by injection for congestive heart failure (CHF).

- Dosing considerations for Forskolin.

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- How does Forskolin work?

- Use by injection for a heart condition called idiopathic congestive cardiomyopathy.

- What is Forskolin?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96999

Cheap 20 mg tadalis sx with amex

No clinical guideline can account for every eventuality erectile dysfunction age 32 buy tadalis sx now, and recommendations should be taken as statements that inform the clinician, the patient and any other user, and not as rigid rules. The clinician remains responsible for interpreting recommendations taking into account the specific circumstances at hand, and for considering whether new evidence might exist that could alter the recommendation. In doing so, the clinician would do well to consider Sweeney’s three levels of significance when applying the evidence to the person in front of them: statistical significance (is the evidence valid? Clinicians can reasonably expect guidelines to be unambiguous about the first and to give guidance about the second, but the third level of significance can only be understood within the relationship between the treating clinician and their patient, and may provide the justification for deviations from recommended management in particular cases. This framework is articulated in terms of: > pathology (the disease processes within organs) > impairment (symptoms/signs; the manifestations of disease in the individual) > activities (previously termed ‘disability’; the impact of impairments on the person’s usual activities) > participation (previously termed ‘handicap’; the impact of activity limitations on a person’s place in family and society). Early interventions are typically aimed at the pathology of stroke, and at limiting the extent of damage at a cellular or organ level. Later interventions seek to modify the impact of the established pathology on the person’s activities and their participation in society. These ‘levels’ always need to be understood in terms of the individual’s physical, personal and social context. It is important for healthcare professionals to keep in mind that although many of their interventions are treating disease at the level of pathology and impairment, patients almost always interpret their illness in terms of its impact on their activities and social participation. Person-centred care should always seek to operate at the closest possible level to the person’s own interpretation of their illness. Failing to meet the patient at their level of understanding always risks a mis-match in goals and expectations that can hinder the response to treatment and recovery. The members of the Working Party (see Guideline Development Group of the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party), were nominated by professional organisations and societies to give wide representation from all the disciplines involved in stroke care who will use the guideline, and including the views of people with stroke and their families. Most members have a longstanding professional interest and expertise in the field of stroke. The Working Party includes considerable methodological expertise in clinical trials, evidence synthesis and evaluation, including qualitative methods and health economic evaluation. Members are required to liaise with their professional bodies and with other experts in the field to ensure consistent professional representation throughout the process of guideline development. The Working Party chair and the editors are very grateful to all members of the Working Party who gave freely of their time and expertise to produce this guideline. Searches, the selection and extraction of studies, and the evaluation of the evidence were undertaken by a large number of people, listed in the Appendices. The three editors are extremely grateful to each and every one of them and the guideline would not exist without their hard work. Scoping of questions within the Working Party followed by multi-professional and lay consultation led to the generation of 165 questions to be searched (see Appendices for full list of questions and search strategies). For topics newly added since 2012 searches included the time period from 1966 onwards; for the remainder of the topics searches were performed from 2012 until September 2015, although some major publications beyond this date have also been included. If a Cochrane or other high-quality systematic review and meta-analysis relevant to a topic has been published within the last 2 years, further searches were not undertaken and the constituent papers within the meta-analysis were not individually reviewed. If there was substantial high-quality evidence available, additional new small trials were generally not reviewed. From the initial searches of 165 questions, a total of almost 2,000 papers were considered; of these, 670 were reviewed. Studies were excluded by evidence of weak methodology or flawed study design, if research was not in people with stroke, or if the study was underpowered to derive any conclusions regarding effectiveness usually by being too small, and studies with fewer than 20-30 participants were typically excluded, depending on 7 the plausible effect size. Differences of opinion regarding the need to review a study in full were resolved by discussion between the topic lead and the topic editor. Evidence was obtained from published studies using the following principles: ‒ Where sufficient evidence specifically relating to stroke was available, this alone was used. In areas where limited research specific to stroke was available, studies including participants with other appropriate, usually neurological, conditions were used. By necessity the paragraph is brief, but justifies the recommendations and explain the link to the primary evidence or the reason for expert consensus being used instead. All studies that were likely to result in the development of a recommendation were assessed by a second reviewer to ensure consistency and reproducibility. One result is that the evidence relating to specific individual interventions, usually drugs, is generally stronger, because it is methodologically simpler to study them in contrast to investigating multi-faceted or complex interventions over longer periods of time. This does not necessarily mean that interventions with so-called strong evidence are more important than those for which the evidence is weak. The ‘Evidence to recommendations’ sections of the guideline explain the balanced rationale behind a decision on whether to make a recommendation or not, particularly for contentious areas, and acknowledges areas of uncertainty. Principal considerations for any intervention were the health benefits to people with stroke, balanced against risks and potential adverse effects. In the many areas of important clinical practice where evidence was not available or uncertain, the Working Party made consensus recommendations based on a collective view, but also drawing on any other relevant consensus statements, professional guidelines or recommendations. The quality and strength of evidence supporting any recommendation was discussed in a meeting of the topic subgroup, chaired by the topic lead and overseen by the topic editor. Lay members contributed to the subgroup meetings, reviewed the outputs and suggested amendments. A draft recommendation was agreed, which was then submitted to the Working Party for approval or wider discussion as necessary. Responsibility for the final adjudication of unresolved issues lay with the three editors and the Working Party chair, with voting as necessary. Although superficially appealing, this system introduces potential bias in the application of the evidence, particularly when it comes to complex areas of clinical practice. Methodologically strong evidence for less important interventions gives the linked recommendation an apparently higher priority than a vital recommendation where the evidence is weaker. The strength depends solely upon the study design and ignores other important features of the evidence such as its plausibility, generalisability, and the absolute benefit to the total population of people with stroke. Grading recommendations in this way fails to give readers guidance on what is important in the wider context. For this guideline, as with previous editions, the Working Party has not adopted a hierarchical grading system for the ‘strength’ of recommendations. Instead, once all the recommendations were finalised, a formal consensus approach was used to identify the key recommendations in terms of their wider impact on stroke, and these are listed in the ‘Key Recommendations’ section. In some instances, the evidence base provided sufficient information about cost-effectiveness to permit a health economic consideration and where this has been possible it has been included. Some of the new and existing recommendations in this guideline will have significant resource implications, and any organisational or financial barriers to implementation are identified within the linked ‘Implications’ sections so that commissioners and clinical networks can consider the means for local and regional implementation and service re-design. Changes were made to the guideline following discussion of the collated responses at a full meeting of the Working Party. Grateful thanks are due to the stakeholders (listed in Appendices) who took so much time and effort to give the benefit of their knowledge and expertise in improving the guideline before final publication. No external funding was received or sought from any statutory, commercial or voluntary body, and the Working Party retains complete editorial independence over the guideline development process and content. The chair of the guideline development group has no pecuniary competing interests. When discussion occurred in relation to a declared competing interest of a member, that member was required to reiterate their interest and, depending on the nature and level of interest as judged by the Working Party chair, was excluded from contributing to the discussion or the development of any related recommendation. The Working Party will be reviewing the evidence on a regular basis in response to submissions from members and constituent organisations, with the first anticipated partial review in 2018. It is anticipated that the previous four-yearly cycle of reviews and updating will be amended, taking advantage of the new digital publishing format to permit interim updates to the guideline in response to significant advances in the clinical evidence. This guideline is only as good as it is because hundreds of people have contributed their comments to drafts and editions since 2000 for which the Working Party is immensely grateful. Clinicians can apply the general rule that if an intervention is not mentioned in this guideline, then it is not recommended for use, and commissioners are not obliged to obtain it for the populations they serve. However, there are many areas where, even in a comprehensive guideline of this kind, it has not been possible to provide a recommendation, including in exploratory or emerging treatments about which there is often a great deal of professional and public anticipation. Any clinician who wishes to use an intervention not considered within this guideline should: − impartially consider whether an intervention that is recommended in the guideline offers an equivalent or better prospect of benefit to their patient; − thoroughly evaluate the available evidence for the proposed intervention, particularly with regard to safety; − investigate whether participation in a clinical trial of the proposed intervention is possible for their patient; − discuss the risks and benefits of the proposed intervention, as far as they are known, with the person with stroke, including a recognition that the intervention lies outside mainstream practice, so that they can make a fully informed decision. Thus it is quite acceptable to offer patients participation in clinical trials which may lead to contravention of the recommendations in this guideline, where such research has received ethical approval and been subject to peer review. Stroke teams should be encouraged to participate in well-conducted multi-centre trials and other high-quality research.

Purchase tadalis sx 20 mg with amex